A section through the writing cabinet

This section is not inspiring me yet. In fact it shows the writing cabinet to be little more than a dumb box with a low door into it. This is the point where a design idea founders or jumps the hurdle into the next interesting level. Nevertheless I don't think that this particular idea can evolve as much on paper as it will when I have the actual materials to hand, and start making all those micro-decisions, as a response to the qualities of the old doors and other elements. Where to cut, where to join, where to paint, where to stain.

A sketch: The Writing Cabinet against a window

This is a sketch of a so-called 'St Jerome', or writing cabinet, drawn positioned in a corner of my living room. It would take on the appearance of a timber box in the corner, with a single narrow door. Access and egress will be easy enough but not convenient, which is part of the point. I am thinking of constructing the box out of old solid core doors, and I have already sourced a supplier who deals in architectural recovery. The doors will not be very expensive, perhaps about $90 each, and they will possess a ready-made patina, which is somehow important to get the 'wood panelled' appearance I am seeking. I think I will need about six doors, and I will take a circular saw to them and reassemble them as a jigsaw puzzle with the joints expressed by narrow elements of new plywood.

You can see that the little writing desk will create a perch sitting just up against the window, which will afford me a clear view of the city ebbing and flowing past my window, about eight metres below me. The floor of the writing cabinet will be raised approximately 600mm above my living room floor, and as such the glass of the window will continue down below the writing surface, finishing about my knees somewhere. The high position of the chair in relation to the window sill should give the feeling that I am perched above the street, in a superior position for surveillance. This is essential for 'dipping out' of the headspace of writing.

You can see that the little writing desk will create a perch sitting just up against the window, which will afford me a clear view of the city ebbing and flowing past my window, about eight metres below me. The floor of the writing cabinet will be raised approximately 600mm above my living room floor, and as such the glass of the window will continue down below the writing surface, finishing about my knees somewhere. The high position of the chair in relation to the window sill should give the feeling that I am perched above the street, in a superior position for surveillance. This is essential for 'dipping out' of the headspace of writing.

The first point of reference

This weekend I am working on some sketches of the study carrol, which I might refer to simply as the St Jerome from now on. The first seed of this idea, of a tiny space dedicated to writing, came from a 2001 visit to Rhinestein Castle, above the middle Rhine in Germany. The castle was charming enough in its way, and possessed a fairy-tale quality - at least it did to this ex-suburban Brisbane boy at large in the world. The moment of clarity came when I entered the small room within the narrow tower shown at the left of the image below.

The room just beneath the battlements is a tiny circular chamber, accessed by a thick timber door from the terrace, positioned beneath the steep little iron stair that takes you up onto the battlement proper. The room contained a writing desk and a chair, and it had small lead-lined windows looking out and down to the River. I opened one, and saw some boats steaming along in the current many hundreds of feet below. The room felt suspended in mid air, between heaven and earth, and its austerity and simplicity impressed themselves upon me. Apparently Kaiser Wilhelm II had used that very room to write in, and while he is not my favourite historical personage I cannot fault his taste in 'perches' for writing. Overlooking the Rhine placed the room on one of the principal arteries of industry and trade, and one of the signature natural features of Germany. The castle behind provided a psychological security, and yet the room itself was tiny.

Basically, I want one.

The room just beneath the battlements is a tiny circular chamber, accessed by a thick timber door from the terrace, positioned beneath the steep little iron stair that takes you up onto the battlement proper. The room contained a writing desk and a chair, and it had small lead-lined windows looking out and down to the River. I opened one, and saw some boats steaming along in the current many hundreds of feet below. The room felt suspended in mid air, between heaven and earth, and its austerity and simplicity impressed themselves upon me. Apparently Kaiser Wilhelm II had used that very room to write in, and while he is not my favourite historical personage I cannot fault his taste in 'perches' for writing. Overlooking the Rhine placed the room on one of the principal arteries of industry and trade, and one of the signature natural features of Germany. The castle behind provided a psychological security, and yet the room itself was tiny.

Basically, I want one.

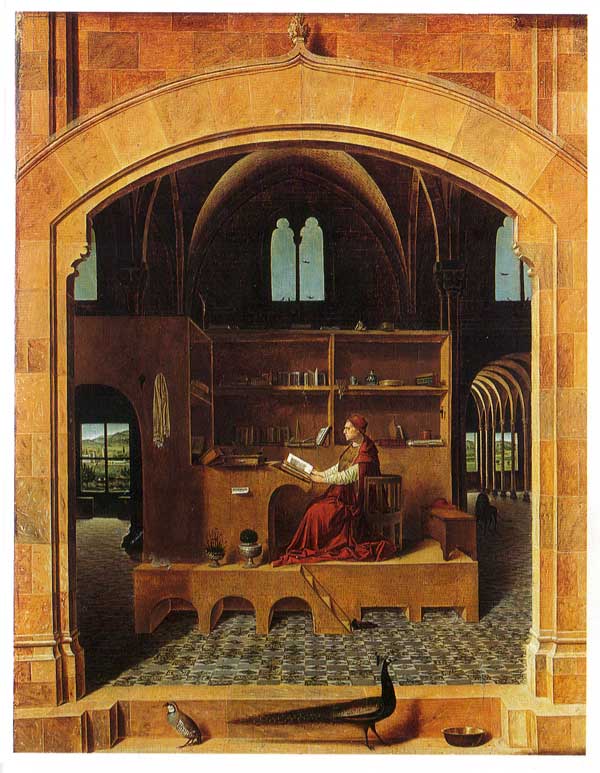

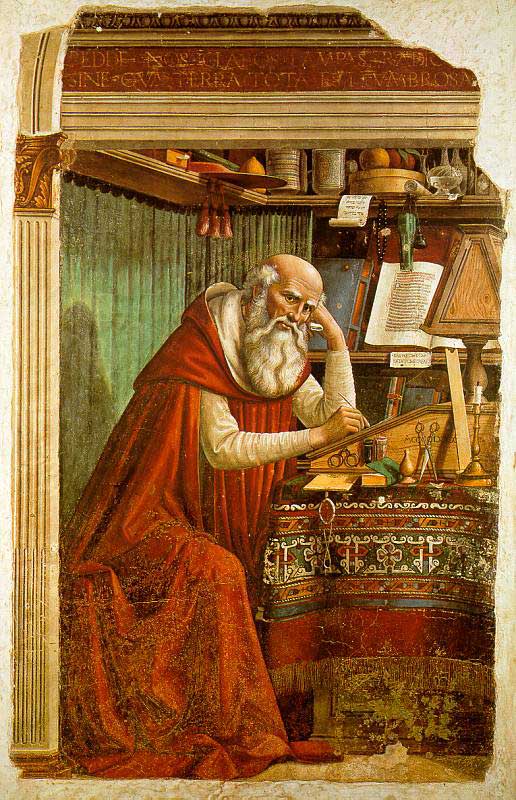

Saint Jerome: designing a personal scriptorium

This is one of my favourite paintings, and it is one of a series of images that are the direct inspiration for a new project, which is the design and construction of a personal study carrol or 'writing closet'. All good design meets some need, and I have two convergent needs that can be addressed with the project. The first is the simple desire to design and build something I can occupy. The second is the need to create a psychological 'bubble' - a delicately balanced room or space that I can go into in order to think and write: a personal scriptorium, or perhaps "physical headspace".

This is one of my favourite paintings, and it is one of a series of images that are the direct inspiration for a new project, which is the design and construction of a personal study carrol or 'writing closet'. All good design meets some need, and I have two convergent needs that can be addressed with the project. The first is the simple desire to design and build something I can occupy. The second is the need to create a psychological 'bubble' - a delicately balanced room or space that I can go into in order to think and write: a personal scriptorium, or perhaps "physical headspace".Have a look at these paintings of St Jerome in his study: they each contain at least one idea that I will use to create my 'headspace'. In the frescoe below I see a pleasant homely clutter of writing and study implements including scissors, books and sheafs of paper. I am particularly interested in the overhead shelf.

The painting below shows the Saint in a more contained, closet-like carrol. It is not hard to imagine this 'study' as a box-like room of sorts, or at least an alcove. This painting is a delight, with the Saint's attendant lion stretching its paw up towards his hand. Again with the pleasing clutter of the man of letters.

This painting introduces a spatial relationship of particular interest: the study or carrol as a timber element you climb onto, in the corner of a larger room, positioned beneath a window. Again with the clutter.

The final painting elaborates the theme: platform of timber, corner of the room, positioned with a window integrated into the joinery. The Dutch style of side lighting is also important.

So that's the inspiration. Watch this space to see where I go with it. It is shaping up to be my most eccentric project to date: good times.

Hints of the black dog

The internet is oversupplied with an oversupply of 'how are you feeling right now', and in some ways I am sorry to add more noise to whatever thin little signal there is that might be out there. Nevertheless, I just thought I would share this sentiment, accompanied by a photograph I took in the park last Sunday. I am feeling distinctly gloomy this evening, despite the fact that it is unlike me to feel this way in the absence of any good reason. No good reason presents itself.

Well, there it is. No analysis, no rationalisation, no particular cause - just a superficial veneer of gloom that will doubtless be gone tomorrow morning. And it is unfair of me to use an image of my dog Lucy to stand in for Churchill's black dog of depression: she is all about wagging tails and happiness. Think I might go give her a hug right now.

When seeing is doing

The Laws of Attraction 1: Pantheon

The Laws of Attraction 1: Pantheon The Laws of Attraction 2: Lyttleton Harbour

The Laws of Attraction 2: Lyttleton HarbourI have been thinking about something that connects both of these images. In fact, I would go so far as to say that these two photographs are depictions of the same phenomena. This is a discussion about a personal experience, or perception: it may not be universal, but it is certainly shared.

One photograph is of Lyttleton Harbour in New Zealand, on the outskirts of Christchurch, as seen from the balcony of a small house. The other is of the Pantheon in Rome. More precisely, it is a photograph taken from the western side of the Pantheon looking over the crowds in the Piazza della Rotonda, who have been drawn to the building like metal filings to a magnet.

That's a clue to what I am talking about. The Pantheon generates a field of attraction - both as an idea, or a story, and as a building. People flock to see it, undoubtedly for a host of sensible reasons: it is so intact, and it is such a fine, direct and unequivocal public building. That might explain why people travel to see it.

It does not explain why the space of the Piazza is so charged, and that people feel compelled to just sit there in the building's presence. People drink coffee and beer, and consume pasta and pizza, in the presence of this building. Such things happen in other piazza(s), for sure - but there is a palpable sense of moment surrounding the Pantheon, similar to the atmosphere of anticipation in a theatre when the crowd is building and the house lights are still up. People sit in front of the building, doing something or nothing. The dependability of this behaviour is unquestionable, and the individual is part of the whole; something is happening.

Then there is Lyttleton Harbour. The working dock shown in the distance, there at the water's edge, exerted a familiar field of attraction on my recent visit. I felt that I could be perfectly satisfied just watching it as the light changed, and much like the cafés around the Pantheon, the houses on the hill are all oriented towards it.

Here's the thing: what is it about these two situations that is able to cut through the jaded, stuporous gaze of the contemporary viewer or tourist with such a potent charge? I am speaking of myself, of course. I am drowning in visual and other sensory stimulation, and yet both of these two situations exerted an influence over me that was almost mesmeric: a sense that to look was to be a part of something happening, that to be looking was to be doing.

What does this mean? I am not sure, but it is there, deep in my gut: the same thing is happening in both photos. I will write about this again, and perhaps speculate as to why architects and other designers expect the 'Pantheon effect' to hold true with every individual work, despite the fact that this obviously cannot be the case.

But if we don't aim to create a mesmerised, enraptured viewer for our design work, what do we aim for? I think it matters. Let me know what you think.

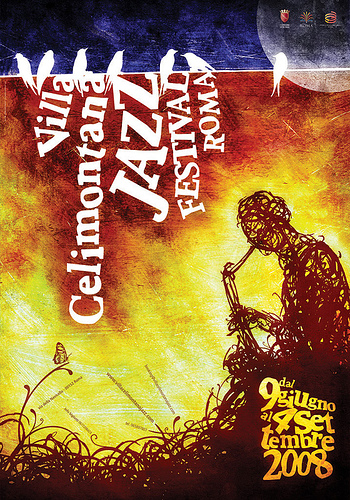

On aesthetic transgression

Why would you not illustrate a jazz festival with a certain aesthetic? Why wouldn't you use a conservative 'American country club' serif font in gilt, with mahogany highlights, to illustrate a jazz festival? I don't mean an ironic aesthetic, but the real thing - uptight and frankly bad. Why wouldn't you do this, and what would happen if you did? I will come back to that last question.

Why would you not illustrate a jazz festival with a certain aesthetic? Why wouldn't you use a conservative 'American country club' serif font in gilt, with mahogany highlights, to illustrate a jazz festival? I don't mean an ironic aesthetic, but the real thing - uptight and frankly bad. Why wouldn't you do this, and what would happen if you did? I will come back to that last question.I am interested in the aesthetic 'force fields' connected to cultural forms, or for that matter any kind of activity...systems of aesthetic orthodoxy, at the edges of which we find the limits of acceptability and the point where the apparent aesthetic permissiveness of the genre or practice is shown to be anything but. The vigour with which such system are protected against 'corruption'.

We can look back in time and think of the Futurists or the first Bauhaus students as idealistic and in some way understand their zealous protection of an aesthetic objective. Somehow I understand, and I sympathise. More than this, I 'get it' visually - I instinctively know when something is 'not Bauhaus-like', even if such a thing is absolutely impossible to define, and I might in fact get it completely wrong. Still, I know that there is a syntax and a system, and that there are rules that extend well beyond the visual or aesthetic. These rules are social and cultural as much as they are aesthetic, in fact.

Which leads us back to this question: what happens if you transgress, if you move beyond the limits of acceptability for a given form or activity? Well, that's pretty straightforward. Ostracism: expulsion from the tribe.

Interesting.

Credit: Photo of poster by Francesco Basile

On pocket watches and the salvage of time

As part of my intermittent and yet ongoing programme of peronal obtuseness, I have begun to wear a pocket watch, and leave all of my twelve wristwatches at home. There are many fine pocket watches available to the contemporary consumer, including an androgynous and unisex Skagen watch with a leather 'chain', but I wanted none of this. The point of wearing a pocket watch in 2010 is not to politely transmute such an anachronistic object from its past incarnations into the present. No.

As part of my intermittent and yet ongoing programme of peronal obtuseness, I have begun to wear a pocket watch, and leave all of my twelve wristwatches at home. There are many fine pocket watches available to the contemporary consumer, including an androgynous and unisex Skagen watch with a leather 'chain', but I wanted none of this. The point of wearing a pocket watch in 2010 is not to politely transmute such an anachronistic object from its past incarnations into the present. No.The point of wearing a pocket watch is to be capable of taking time in hand, literally, and then putting it away in your pocket. The first of four watches I have purchased as part of this programme is a Swiss watch with a quartz movement. After I had purchased it I realised that this was a mistake. For the experience to really resonate with my position on this topic the watches need to be mechanical mechanisms, and requiring hand winding.

As a result I have purchased three additional watches, which I intend to wear in rotation as the fancy takes me. The first is a French Charles Hubert watch not dissimilar to the one illustrated on this page. The second is a rather more expensive German watch, made by Kienzle, finished as a skeleton case. The third is something of a gem, it is an Elgin watch from 1915, which carries an engraving explaining that it was awarded as the first prize in the Los Angeles Amateur Boxing Championship of that same year. The engraving is very fine, possessing the quality of copperplate handwriting.

So with this small arsenal of timekeeping devices I intend to take charge of my time, safe in the knowledge that if I choose to stop winding the watches, then time will dilate and run down until it finally creeps to a halt. There is something inordinately comforting about this: I am implicated in the entrapment of modern timekeeping, and yet I can make the decision to let it all grind to a halt. Working as I do in deadline-focused environment, and facing the relentless pressure to constantly gain efficiency, there is a grain of comfort in this.

What do you think: futile gesture in the face of crushing obligation? Yes, it probably is.

The Melbourne Urban Photography Project: first excursion

Of the 46 photographs I took on Sunday, this is the most successful

Of the 46 photographs I took on Sunday, this is the most successfulI have decided to devote a modicum of my time to taking photographs of the Melbourne Central Business District and surrounds, as a smaller part of my larger Journal project. The Journal project is quite simply a diary exercise, which involves the creation of a hand-written diary in two notebooks (one large and one small) and this blog, as well as a couple of other online repositories. The Melbourne Urban Photography Project is the visual part of this larger enterprise. My first outing was on Sunday, when I walked with a friend from the city grid across to North Melbourne, an adjacent suburb. This photograph was taken quite near my apartment, on the concrete apron in front of a large private carpark.

Take that, minimalism...

Detail of a half-dome in an Iranian mosque

Detail of a half-dome in an Iranian mosqueThis photograph of an Iranian building was posted by the blogger pesaretabrizi, who according to his website, is based in the UK.

Check out his full collection of images here.

Thinking by the Bay

Dimmeys ladies on the beach at Sandringham, 1911

Dimmeys ladies on the beach at Sandringham, 1911Some things are hard to explain. In fact, some things are so difficult to explain that they rarely get explained in any but the most cursory, conversational setting. I was thinking about my freelance journalism gig the other day, and it occurred to me that to explain something that is subtle, nuanced and complex is much easier than explaining something ordinary or mundane. Nuance demands elaboration: the mundane does not. This can place the reader or listener in a situation where they may misunderstand an explanation simply because it is so surprising that the attempt to explain is being made in the first place.

Which is all a little abstract, so let me give you an example. On the weekend I was driving along the edge of Port Phillip Bay heading south from St Kilda. To the west the sun was setting over the Bay. To the east we skirted the edge of the popular beachside suburbs, zipping past a seemingly endless march of bloated, oversized and poorly styled houses facing out across the water, directly into the setting sun. Periodically we would pass an old hotel, an intrinsically fine building that had been renovated (but not restored) to within an inch of its life. It was these historic hotels, embalmed in acrylic paint and ugly signage, that first put me in mind of this difficulty of describing the mundane.

The work done on the hotels is almost unfailingly bad. This is immediately apparent to the trained observer. However, explaining why they are bad to a lay person is by no means an easy task. After all, they are ‘nice’ and in excellent condition, they have obviously had money spent on them, and they are undoubtedly genuine establishments - bona fide hotels, alcohol, bottle-shops and all - just as they were when they were first built. Nevertheless, there is something very wrong with nearly all of them, and it wouldn’t matter except that the buildings beneath the gloss are often conspicuously grand and fine, and in excellent locations.

Why bother trying to explain this to the lay person at all, you might ask? That is an interesting question. I do not subscribe to some tedious ideological position that sees information or knowledge as some Protestant ‘good’ to be foisted on people for their ‘own good’. The Australian Institute of Architects might beat the drum of ‘public education’, but I am not a sandwich board and really can’t be bothered, on the whole. However, explaining design-related things to non-designers, particularly intelligent ones, is an excellent discipline as it requires skill, clarity and precision to make the point. It also requires that you abandon your reliance on jargon - that strange verbal shorthand used (abused) by ‘communities of practice’ who share a common education, field or technique. Specialists, in other words.

Speaking about architects, amongst whom I spend most of my professional life, I have observed that in most cases jargon is not used to streamline communication so that the professional exchange can ascend to a higher level in a shorter time - as one might hope. Jargon is used by architects as a method of indefinitely suspending their disbelief in the face of claims and concepts that lack rigour, lack precision, remain untested and can be, frankly, unbelievable if rendered in plain speech. In other words, the waffling architect is prone to believing their own gobbledygook. However, in order to do so, he or she must continue to speak in tongues at all times, and never condescend to answer the simplest of questions, useful in almost all cases when an architect has just finished stating an idea with conviction: ‘what do you mean by that? ‘

The other use of the lay-person as recipient of an explanation is that it draws out the obvious. Things that are obvious to a designer usually are not obvious to non-designers, and to state the obvious is an excellent start to an explanation of complex matters. ‘Obvious’ is misplaced in this usage at any rate; what we really mean by ‘obvious’ is ‘assumed to be so on the basis of self-evidence’, with an educated specialist doing the 'assuming'. A funny thing happens when you state your assumptions: suddenly they don’t seem so ‘obvious’ after all. At least I assume this to be the case, as it is precisely what I experience when I state the obvious in the face of a design problem. Is this a shared experience?

In my design journalism I like to adopt the expectation of an intelligent, non-specialist reader as the gold standard. The main result of this approach is not merely a prohibition of jargon: it forces me to make a fundamental shift in my thinking. Ultimately it is a personal judgement, but I don't think that most intelligent non-specialist readers have much interest in the things that specialists focus on. As specialists we need to notice this, as despite our undeniably impressive bodies of knowledge, we continue to focus energy on things that have little or no resonance with the lay person. The perceived 'ugliness' and 'unfriendly' aspect of many architect-designed buildings is one such area. Architects do not discuss this, and the unspoken assumption seems to be that if 'they' were better educated, and had cultivated 'their' taste above the common denominator, then 'they' would 'get it'.

Is that so. I have long suspected that architects of the third millennium avoid decoration, complicated, florid detail and legible rooflines so much - because they do avoid them - because they involve risk, and a visual composition that incorporates complexity is so much harder to control than monolithic, minimalist simplicity. Both are equally hard to do well, but only one of the two is easy to do inoffensively well.

I wonder what the ladies of Dimmeys, the venerable Melbourne department store, shown here on the beach at Sandringham in 1911, would have thought of the post-millennial renovations of the nearby hotels? How would they have seen the stripping out of detail, the dismantling of the complicated rooflines, the removal of polychrome colour schemes in favour of monolithic blocks of colour, and the obsessive sealing of the verandahs with impenetrable sheets of glass, all in the interests of replicating the bland, air-conditioned uniformity of the rooms within? Isn't the whole point of a verandah to be taking the outside air, and yet with some of the comforts of a room - a good chair, a side table for your Pimms and lemonade? Apparently this is no longer the case.

Many architects reading this should probably disregard what I say, although they certainly won't wait for my permission or encouragement to do so. If not they might find themselves designing buildings that their grandmothers could relate to - and that, surely, would signify that the taste war has finally been lost.

Wouldn't it?

Not Serious Design

I’ve been thinking about design and design journals. In the interests of full disclosure, allow me to first say that I regularly write for the Australian design magazine Artichoke, which is the Journal of the Design Institute of Australia. Fortunately for the members of the Design Institute and I, Artichoke routinely avoids falling into the category of journal that I discuss in this post. I like writing for Artichoke because my colleagues on the editorial staff seem happiest when I am speculating about what design might be, as understood through various projects, and not merely what it is. I try to regard the design process as exactly that, an interesting process that has had results, and not a closed or stable system that periodically gives birth to polished gems.

I’ve been thinking about design and design journals. In the interests of full disclosure, allow me to first say that I regularly write for the Australian design magazine Artichoke, which is the Journal of the Design Institute of Australia. Fortunately for the members of the Design Institute and I, Artichoke routinely avoids falling into the category of journal that I discuss in this post. I like writing for Artichoke because my colleagues on the editorial staff seem happiest when I am speculating about what design might be, as understood through various projects, and not merely what it is. I try to regard the design process as exactly that, an interesting process that has had results, and not a closed or stable system that periodically gives birth to polished gems.It is a subtle distinction, perhaps, but I am old-fashioned enough to believe that good journalism should expose and explore subtle distinctions. ‘What might design be?’ is a question. Describing and sharing what design is has value in encouraging people to discover new wrinkles of this fascinating pursuit, but it is not a question: it is the provision of an answer. I boldly suggest that questions are far more interesting than answers.

It seems to me that if we approach this particular question with an open mind then the situation is very different to that closed, rather self-congratulatory impression you get from many design journals. This impression is painfully apparent to the uninitiated, who in my experience are more likely to be respectfully intimidated than skeptical and disdainful, as perhaps they should be.

Reading much of the design press, you can also get the impression that the producers have forgotten that ‘cool’ and ‘good’ are not the same thing. ‘Cool’ and ‘good’ are not the same thing. If the overwhelming impression an intelligent non-designer gains from a magazine is 'hey, isn't this cool, and aren't we cool, you and I, for knowing it', then something is amiss. The moment's best furniture, clothes, objects, bars and restaurants - most design-related organs are more of a latter day 'gentleman's outfitters' updated so that the bloodless, androgynous urban dandy, he or she, has all they need for an aesthetically better life. A better German bike courier's messenger bag, better Spanish shoes, better Japanese stationery: artfully generic and label-free, or crafted from industrial discards and finished with fine details? Take your pick.

This might offer all the high-calorie comfort and entertainment of shopping, but those non-mail-order catalogues (can you tell me the trade price on the B&B Italia sofa on page 85?) rarely stoop to posing uncomfortable questions, or airing awkward truths. The first among these must surely be the relationship between wealth and design. It's not good, it's not bad, and it's not discussed.

The 'Andy' sofa, 370 cm long, 3-seat with a chaise lounge upholstered in a mid-range fabric, costs $AUD27,325.00. That is $US25,374 by today's exchange rate. What does it mean to spend more than $25,000 on a sofa? Is there any way that can be a reasonable thing to do? The Federal minimum wage decision for 2009 in Australia is an income of $AUD543.78 per week. So the sofa is worth just over 50 weeks of the minimum wage, virtually a year of person hours. You may think I am mounting some socialist argument about the distribution of wealth by pointing this out; I confess to such a bias, but that is not really my point. My point is one of perspective and relativity, and the conditions that provide insight to the designer. By pushing design into such stratospheric heights, we disconnect our focus as designers from the experience of the vast majority of people in our society. Is that ok?

Certainly, in order to do so, we must avoid uncomfortable questions about wealth and privilege, and the bearing these things might have on aesthetics. However, I am less interested in the moral implications of that than in the fact that we are excising from the ‘world’ of design much of those things which quite simply make up the world. Worse crime still: it’s boring. Boring to avoid straying from the ‘best of the best’, to censor what constitutes ‘serious’ design.

Forget about the morality of it for a moment, this isn’t just about morals or even ethics. What are you buying when you spend so much? An argument can be made that quality takes time and costs money, and that a brilliantly crafted designer piece will last far longer, and perform better, than the cheaper alternative. That is almost certainly true, and I also wouldn’t like to see the working designer unable to reap the rewards of their creativity, knowledge and training.

But again, it is a question or relativity. Let’s be honest here, there has to be a point where this argument fails to hold water, and become mere cover for privileged indulgence. Where does the line fall? Three times the cost of a functional alternative? Ten? Twenty? Someone tell me: is a bona fide B&B Italia sofa worth 50 weeks of the minimum wage? Am I the only one who thinks this is all a bit distorted?

I have in my apartment a very awkward object. It certainly does not constitute, and would not ever be considered, ‘serious’ design. I suggest that it hasn’t been designed at all, at least not in the conventional sense. It is a timber easel, hand-carved, standing six feet high. What I like about this easel, on loan from a friend who couldn't bear its lack of Scandinavian minimalism, is that it would never appear in a design journal. Never. It doesn't even manage kitsch, although it might manage to figure in a social realist photograph, perhaps one taken in Kentucky or Miami.

This makes it a fascinating object to me, and while I won’t defend its aesthetic qualities (should I have to?) I will say that I like having it around. The reasons for this have a lot to do with what it evokes for me, and the pleasure I get from the design-canon-violating aesthetics of hand-carved timber. The thing even has flowers carved into it, and part of it appears to be shaped like a pair of spectacles, or breasts. (The easel pictured here is not the actual one, but you get the idea.)

Does this damage my credentials as a ‘serious’ designer? Probably. What a relief that is.

What happens in the space between thoughts

Have you ever been startled by an audible but faint noise, or the unexpected movement of an inanimate object? What is going on in your consciousness when this occurs?

Have you ever been startled by an audible but faint noise, or the unexpected movement of an inanimate object? What is going on in your consciousness when this occurs?The studio is quiet this week, people are hushed and the phones generally aren't ringing. I was drawing, using the computer to copy ethereal digital circles of pale green, when the roll of yellow tracing paper sitting on my desk slowly unfurled in my peripheral vision. It made a tiny noise, a kind of scratchy wheezing as the edge of the trace was drawn across a piece of creased bond paper on my desk.

It happened in one of those fleeting micro-moments of sudden stillness, and due to the meditative nature of the drawing exercise I was immersed in this strangely drawn-out, tiny, sudden movement startled me. This was a personal moment, a tiny sliver of time of about three seconds, and yet I felt my perception suddenly shift as if the floor had dropped out beneath my feet.

Call me odd for saying so, but I like that sensation. It is the diametric opposite of being in control, and I only ever experience it when I am relaxed. I don't think the insignificance of the experience (for it is certainly insignificant) disqualifies it from consideration. It is a cliché to say that life is made up of such moments, but it remains true nonetheless: just hanging around and being is quite a rich experience, if we can tune our senses to its subtleties.

Of course, most of the time I, and I imagine you, are far too busy to smell such invisible roses. While we are on that topic, and speaking of clichés, have you ever stopped to smell the roses? It has become something of a superstition that I must do this whenever a rose presents itself. It’s true: I really do. This obsessive little habit has rules, though – cut roses do not invoke the reaction, and going to a rose-garden would also not satisfy the conditions of the act, as it would be far too obvious. However, if I am on site, or wandering out in the world, and I unexpectedly come across a rosebush, I almost always stop to smell it.

I attribute this to the notion that much of my inner life is lived in language, and a phrase ‘stop and smell the roses’ is something of a provocation or challenge, as well as being a well-worn cliché. I experience a tiny moment of reflective pleasure when I am able to make physical and real a concept with a meaning so debased and diluted that it scarcely conjures the image of a real rose when said aloud. It is as if the act strips the phrase of its cliché, if only for a moment – and the words are recharged with descriptive power. Don’t you think that is fascinating? In a similar vein, there have been days when I have left a lunch appointment and said ‘back to the drawing board’, and meant it quite literally.

Like most of the things that fascinate me, I have no idea what this means. Yet still, I like it.

Atmosphere and image

I am looking at a photograph that I took in Piazza San Marco in Venice in November. You can see it above, with its cheerful yellow chairs clustered around tables set with crisp linen cloths. I am looking at the image in a large digital format, much larger than shown on this website, and by concentrating on the details I am taken back into the moment. The moment was shared with a friend who had accompanied me on a walking tour of the City that day, and I can vividly remember the sense of the place, the temperature and humidity of the air, the flat whiteness of the sky and a thousand other details that are not experienced as such, but woven together to create a unique 'atmosphere'.

Images can be transporting in this way, taking us to far-off places, but to overstate their power to do this is romantic at best and misleading at worst. More often than not the power of the image is heavily diluted and diminished, and I attribute this to two things - the saturation of our visual environment, and the overstatement of the power of imagery alone in the absence of other sensory cues.

Marking this fact is seen as a bit superfluous, and generally the creative professions just get on with the business of image production and manipulation. Nevertheless there is something in it, something about the notion of the image as a single weapon in a broader arsenal that is not often discussed.

I am always mildly anxious while taking photographs. This is not an emotion inspired by a fear of making a poor image, something I avoid most of the time and can tolerate passably well when it does occur. It is a different kind of anxiety, an awareness of the moment being enshrined and frozen, almost as if I am scared of what might be captured by the lens. I tend to frame the shot with something of an aesthetic sense, but quickly, and not dwell on details that are plainly visible to me at the time, by virtue of my being there. I tend to quickly frame and fire off the shot, and just wait to see what it yields later on, rather than spending a moment pondering what I am seeing and considering how it could be framed.

When this goes well there is a spontaneity to the imagery, but when it does not go well the shots are poorly framed, or I see later that an opportunity was there but overlooked. The issue of making good or poor imagery is not really the point I am interested in, as I feel that closer attention to the technique of observation and framing helps this immensely. I am far more interested in the experience of marking a moment in time by capturing its specifics, and the relationship of this to the atmosphere of the place.

'Atmosphere' is not something that serious architects or designers discuss very often. It is seen as a non-professional or amateurish word, more suited to the realm of the decorator or Friday-night home improvement television programme. I disagree, and think that it is a fine word, and very useful for encompassing a broader spectrum of personal experience linked to place than the more restrictive 'style' or 'language'. What I really like about the word 'atmosphere' is that it is rooted in the experience of the person in the place, whereas more 'serious' technical architectural terminology is almost always focused on the characteristics of the space, building or place being experienced.

This is not a subtle distinction. To use the example at hand, Piazza San Marco has architectural and spatial characteristics, but to consider it as being merely the sum of those characteristics is to deny the richness of the actual experience of the place. The Piazza is never experienced independent of the temperature, the humidity, the quality of light, sounds, odours, movement and the presence of other people and the different things they are doing. In fact there is a wealth of nuance and subtlety - and an abundance - to the atmosphere of the place, and it is constantly changing. it is there to experience, if we can only tune our awareness to soak up the atmosphere in all of its parts.

Architectural discourse - the way architects speak to each other - is heavily censored and restricted, and this affects how we think about what we do, and how we discuss it with outsiders. It is partly the choice of words, driven by a sense of what is professionally orthodox and appropariate, and what is amateurish and 'beneath' a trained professional. Outsiders should not underestimate the designer's fear of being seen as 'uncool', either - I'm quite serious about that. Designer Bruce Mau acknowledges the corrosive power of 'coolness' in his studio's excellent Incomplete Manifesto where it is put like this:

14. Don’t be cool.

Cool is conservative fear dressed in black. Free yourself from limits of this sort.

Visiting Piazza San Marco is undeniably a cool thing to do so perhaps my example is a poor one, but nevertheless, an 'uncool analysis' of what this photograph taps into points to something quite outside an orthodox architectural discourse. If the photograph transports me to another time and place, it is not because I have captured the 'essence' of the place in my image: it is because there is enough detail in the image to evoke my memory of being there, reminding me that I was footsore, cool but not cold, suffering from the glare of an overcast day and overwhelmed by the simple wide-eyed fact of being there for the first time. All of those things forged the atmosphere of the place as a personal sensory and visual framework: from that comes the emotive and evocative charge of the image.

This quality of 'atmosphere' exists everywhere, and not just in photogenic tourist destinations: how it accumulates over time and with the familiarity of the everyday is of particular interest to me. The density of experience it amounts to is so common that we are usually blind to it, and we become insensitive to the places we go every day. Nevertheless, the subconscious or unconscious mind is always assimilating detail, and over time we build up a rich, dense and nuanced composite picture of the places we know. If you doubt this, think now of a place you knew and liked - or disliked - in childhood: the formative memories can be the most potent.

Designers use images to create. We use photographs and drawings to capture what exists, and to visualise and make real what does not yet exist. If we as designers can somehow more closely link the intention of the image to a sense of a place's atmosphere, we may find ways to describe an emotional and atmospheric reality embedded in what exists, and yet evocative of what we wish to create. This might be fertile new ground.

Instance of the flea

Something small to cause something big

Something small to cause something bigIf we are to believe the code of the Samurai as filtered through the narration of the movie Ghost Dog (I wasn't interested enough to check primary texts) then thinking about death is not a bad thing to do. Now let me get one thing straight, right up front: I am not 'half in love with easeful death' as Keats put it, and I am pleased to report that I have never contemplated suicide. There but for the grace of the gods go I. This post is not about such vexed matters, and I would refer anyone troubled by thoughts of self-harm to Beyond Blue, a good site for help and information.

No, this post is not about hastening the approach of death, something I am keen to avoid. This post is about life, and the enrichment of same that can be yielded by a quiet, sober awareness of death's inevitability. This is certainly not an original thought, but an important one to touch on early in this blog nevertheless. At any rate, too much time is spent avoiding thinking about obvious or unoriginal things: I have expounded my thoughts on this issue here. Death certainly fits this category.

So what's with the flea? Of course, there is the obvious - this tiny agent of chaos was instrumental in the decimation of the population of Europe in the mid 14th Century. How many prodigies of art, music and science were culled from our history? Several centuries later the poet and polymath John Donne (1572-1631) understood the metaphysical potential of this diminutive creature, although in his case the metaphor was one of sex, evoked by the image of the mixing of blood in the flea's mouth, rather than death.

There is something about these two aspects of the flea that seem intrinsic to its nature. It is a mere fleck or mote, and yet with a long enough lever it may shift the foundations of the entire world. Death is never far away, and as vain and superfluous as it is to say so, I think that's ok. It's not like any of us have a choice about it! The presence of death in my personal network over the last two years has made the following very clear: some things matter, and many things really don't. Friends and family fit the former category, while career and most other things do not.

The failure of design

I've been thinking about what constitutes good design, and find that it is a difficult question to answer.

Design would appear to be the new mantra, in business and in the 'lifestyle industries', to use a ghastly phrase. 'Good' or 'serious' design is assumed to always add value, and it is assumed by designers, and increasingly the educated general public, to be always highly desirable to it's alternative. However, what this alternative might be is by no means clear, and in that I detect something interesting.

Designers will tell you that the opposite to 'good' design is 'bad' design, where something has been shaped or put together in a way that responds poorly to its intended purpose and meaning. That seems reasonable, but I am not sure it holds up to scrutiny. What if the opposite to 'good' design is something far more incidental? Could the opposite of 'good' be not so much bad as 'whatever' - a genuine randomness that results from the inevitability of form in objects despite the absence of authorised, orthodox design intentions? Good design can be judged against a whole host of factors which might include the intention as stated, the function as demonstrated in use, or the aesthetics and shape. How would we judge 'bad' design? For that matter, why do we feel compelled and authorised to judge it?

They Mythical Modernist has a ready answer to this. The MM might argue that when it comes to things made by people, 'all is design, and all is designed', whether we like the results or not. If this is true then it is reasonable to judge all objects and forms by the same standard, and if we do that it stands to reason that we as 'good designers' would decry the poor standards of the design of most objects and buildings we encounter.

There are a couple of problems with this. This claim of the omnipresence (or omnipotence?) of 'design' is a kind of megalomania that has everything in common with the modernist definition of urban design as the imparting of 'right form' to whole neighbourhoods and cities. Then there is the problem of applying the 'same standard' to good and bad, or unintentional design. How is this standard determined?

The standard of 'right form', also known as 'serious design', is determined by common agreement - leading example and its enthusiastic approval - and codified into a visual syntax or codex policed by the high priests (the 'leading' designers), whomever they might be. This forms a kind of gold standard against which most things can be measured, and in the measuring some things are deemed as 'good' and some as 'bad'.

One problem with the gold standard of 'good design' is that it inevitably changes over time. Nevertheless at any given time it is considered immutable, a yardstick against which we can separate 'serious pieces of design' from their poor cousins. Any architect would admit that a 'really good building' of thirty - or even ten - years ago would look dated and be considered inappropriate now. Strangely, this is not seen as a flaw in the method of determining good design: it would seem that the codex has a convenient 'out' clause, where older projects can be authorised by virtue of their dated context.

Despite some very obvious structural cracks, it is plain to me that some designers, architects in particular, believe that the 'good design' standard has some gravity and authority. They firmly believe (or perhaps assume) that the world overall would be a substantially better place if only it was designed by them and their colleagues. There is not much evidence to support this view. The most beautiful and engaging places I have seen ended up that way largely without architects, with the possible exception of key buildings of particular significance. In fact the profession as it is currently defined is very young, and many buildings we attribute to architects were actually conceived and designed by dilettantes and artists. Architects and other designers also seem to overlook the megalomania of this idea: should our entire environment really be wholly determined by one tiny and not particularly representative segment of our society? Does that even look right as an idea on paper? I think not.

Despite the fact that we are bound in by ugliness on all sides, I don't think that giving the whole equation to the architects is the answer. I can only think of a handful who do work I like, for a start. Fortunately for us the world is a diverse and complex place, and so far orthodox design has failed to encompass all of human life. That's a good thing, because I suspect that the seeds of our future world - the lightning bolts of brilliance and breathtaking change - will not first be seen on the pages of a glossy design magazine.

I've been thinking...

Welcome. This is it, post one of A Flawed Mind, the blog I am dedicating to the deceptively simple phrase 'I've been thinking...'

I am a thinker by habit, but it has not necessarily always been a comfort. In fact I was recently told by a friend that I tend to 'think a bit too much'. This is undoubtedly true, and in the past I suffered from a far more obsessive strain of thought than I currently enjoy. There were dark times, and I occasionally wished that my head would explode and be done with, at least in a figurative sense.

Despite the shadows, happily somewhat distant now, I continued to prize thinking highly. Thinking, and its more casual cousin 'reflection', are central to my job, or jobs, which have become a personal vocation. I am in the creativity business, working right now as an architect and an itinerant freelance journalist. Both crafts require a surprising amount of reflection, or at least they do the way I practise them. Up until recently I was also a design teacher at an architecture school. That too required a great deal of thought before, during and after contact with students.

Now entering the third year of a self-imposed sabbatical from teaching, I find that I have a great deal of extra time in the week, and I am keen to use this time to lead a richer life. To help make this happen I have been slowly re-engineering my life (and my lifestyle) to include more time and space for reflection. Reducing my daily total commute to (literally) about three minutes is a great improvement on the previous record of three hours a day, and this too has liberated my body and mind for many more hours each week.

Thinking and reflection (I might use these terms interchangeably in this blog, but not all the time) are only possible, of course, if they are nurtured and fed regularly. This requires a commitment to reading, looking, listening, photographing, writing and drawing on a regular basis. I am trying to dedicate more of each day to these activities. Fortunately may day job includes most items on the list.

Private reading and listening are particularly important, and I can generally do both every day. I am indebted to two quintessentially American and quintessentially 'new economy' business ideas for the enrichment of both activities. For reading, in addition to the many physical books I purchase I have just got my hands on an Amazon Kindle. This is an interesting device, and I have already subscribed to the MIT Technology Review, Salon and the Times Literary Supplement, just to kick things off. In fact the Christmas shopping season just ended saw digital books for the first time outsell physical books on Amazon: could the oft-predicted e-book revolution finally be upon us?

For listening purposes I rely on one of the most successful internet startups of all time, Audible.com. This fantastic subscription service for audiobooks and other listening goodies has managed to secure $US20 of my personal funds each month for about three years now, and I have enjoyed interacting with an online business that actually does create new value where none previously existed. The whole adds up to more than the sum of the parts.

On a domestic front Radio National remains the stimulation source of choice. Chafing at its perceived intellectual authority I recently tried to pen a polemic entitled 'Why we must turn off Radio National and start thinking for ourselves'. Good soundbite, but in the process of researching it I increased my listening time, and came to the conclusion that Radio National actually is generally good for my brain.

In case this is all sounding a little too highbrow (and on second reading of the above, it is) let me hasten to introduce you to the soft, stripy underbelly of these more intellectual habits. The 'underbelly' is where I attend to the workings of the subconscious or unconscious minds, and for reflection to occur these 'other' minds need their own kind of feeding and love. The techniques I prefer all have these things in common: they are apparently trivial, superficially time-wasting, gently distracting and largely harmless. Three such techniques are 1 - mindless television crime drama in general; 2 - watching endless repeats of The Simpsons; and 3 - driving in the country while recording rambling, unfocused monologues grounded in stating the obvious. These all serve a purpose, and that purpose is to occupy the conscious mind so the unconscious, or subconscious, can go to work. This is the reason that you always remember a forgotten name when you have stopped trying to think about it directly. But you knew that already, I suspect.

And what sterling work the subconscious can do if it is only left alone for a spell, every now and then. This leads us of course to the thorny issue of creative problem solving - but that, as they say, is a whole different kettle of poisson. And it is a kettle that we will stir together many times as this blog evolves. Thinking keeps my dog and cat in expensive imported dry vittles, and me in sparkly drinks and party pies, but it's not all work. Ultimately it is quite fun to spend your time thinking about stuff and working things out. I recommend it as an ideal vocation.

So that's it: post one. Join me again for the next instalment, all in good time.